I was born and raised in Raleigh, NC. Though my origins are from North Carolina, my summers were spent in Philadelphia. Riding trolley cars, eating pretzels and water ice and fighting with my sisters about who was going to ride in the front seat when we went downtown, are memories I hold dear. My mom and dad were from Georgia and South Carolina respectively and chose to remain in the South after living in the North for short periods. However, three of my mother’s siblings and several of my dad’s cousins migrated to the city during the 1940s. Annual summer excursions to Philadelphia were welcomed respites from Southern life. Visiting Philadelphia was exciting, but I missed so much about my Southern community. The community of my childhood was multigenerational, segregated, vibrant, and was a safe haven from the onslaught of individual and structural racism. Collective cooperation where older people or elders were engaged participants in community life was an essential element. Elders were seen as useful and imparted wisdom to the next generation.

My childhood experiences were enriched by having significant relationships with aging adults. They helped shape my identity. Their stories enraptured me and helped me find my place in a broader world by connecting me with history. These neighborhood surrogate grandparents offered discipline, delights and stories of times gone by. I was struck by their courage, faith and strength often in the face of adverse, hostile circumstances. Mother Thorne, the loving, firm grandmother to all the neighborhood children, was capable of delivering powerful messages in just a few words. I vividly remember a conversation with her in which she stated, “It’s not what you’re called, but what you think of yourself.” She affected me deeply conveying a message I’ve never forgotten.

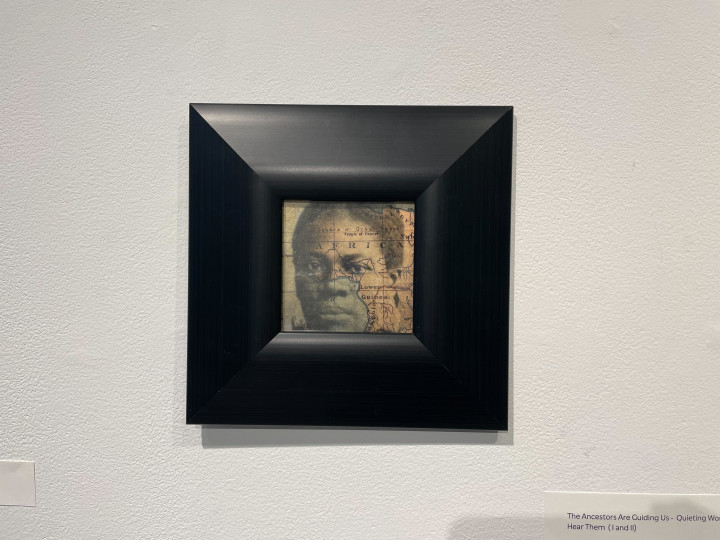

Upon moving to Philadelphia, listening to and capturing the stories of elders was a natural way for me to connect with the city. Being Southern in my folkways provided a bridge for them to share stories about the places from which they came. In 2014, after several conversations with elders, I began collecting stories of African American seniors for the project Journey to Sanctuary: The Philadelphia Story of Faith and Transformation of the Second Great Migration of African-Americans from the South. After receiving a planning grant from NEH in 2018 to implement an exhibition that artistically portrays the themes from the collected stories, I realized that I didn’t have the artistic background to bring the project to life. Pursuing my MFA has been the ideal experience for me to move the project Journey to Sanctuary forward. The MFA in Progress exhibit reflects my passion to create spaces for intergenerational connectivity and portray the value that elders have added my life. Journey to Sanctuary is a lens through which subsequent generations can learn about their connections to Philadelphia’s history of episodic era of American history.