Above: Jonathan Nevair (pen name of Dr. Jonathan Wallis, Professor of Art History and Humanities, Moore College of Art & Design).

Part of the joy of working at an art and design college is that most of the faculty have personal projects outside of their teaching. In the Moore Admissions office, we get VERY excited when we learn about a faculty member’s personal project, and even more excited when it’s something we can share with the general public. Moore’s Liberal Arts professor Jonathan Wallis has written a space opera series under the pseudonym Jonathan Nevair, and it’s official: There’s a fan club in the Admissions Office. Do you like Star Wars? Do you like J.R.R. Tolkien books? Do you like fantasy art? Then these books are for you. As I read the first novel, Goodbye to the Sun, I thought about the Liberal Arts program here at Moore and how quietly influential it is on the broader Moore community. Recently, I had the opportunity to sit down with Jonathan Wallis, aka Jonathan Nevair, and discuss his series, Wind Tide.

Julia Perciasepe: Have you always wanted to write a book or be an author?

Jonathan Wallis: I dreamed of it, but I never took it seriously as something I would do until 10 years ago. I tried to write a fantasy book, got a little way in and stopped. And then a good friend of mine, actually a well-known curator, Nato Thompson, wrote a fantasy novel and I beta read it and gave him feedback. As soon as I did that, I was like, I want to do this. I wrote a science fiction novel and it will never see the light. It was me getting my literary sea legs, learning how to write a novel. Don't give too much exposition, think about pacing, make sure you world build accurately. As an academic, I have a lot of experience writing but I was so used to having to rely on facts and evidence, whereas in fiction, there was this incredible liberty to invent things.

Wind Tide (futuristic city by Zishan Liu)

JP: Would you say you found your literary voice in that unseen novel, or have you found your voice with the Wind Tide series?

JW: I would say I found my voice with Goodbye to the Sun. In my first novel I was holding back a lot. I got good feedback from a literary agent who read a partial submission. They said they really liked my world building but they didn’t emotionally connect to the characters. I took that to heart and I did research on putting emotional investment into readers through your characters. And then I went for it. I put my heart on my sleeve and was like, I'm just going to write. The other thing that helped me was reading The Fifth Season by N.K. Jemisin, part of the Broken Earth trilogy. She's at the forefront of what everyone's doing in the field. That book was written in a really interesting range of voices, including second person, which is really unusual, and there was such an emotional outpouring from the character—almost like a eulogy. I was taken by that and I started to be more honest and vulnerable. And, through that, I found my writing voice.

JP: What type of research did you do to build your worlds?

JW: I did research on really weird things. You need to know how wind energy works, so you need to understand what kind of topography and geology and ecosystem would generate high winds. I also did research on language, especially with regard to dead languages and the way that they influence living languages. I am a science-fiction author but I am not a hard science fiction author. I'm the Star Wars approach. For me, the story is more about the character going through a struggle in a galactic empire than it is about how this galactic empire works on a scientific level. I'm interested in how it works on a cultural level.

JP: I want to ask you about the phrase “space opera.” Can you tell me what that is?

JW: Space opera is a sub-genre of science fiction that takes place in a cosmic space. It tends to be vast in scale so that you're traveling across great distances, and it usually involves space travel. Most space opera is more focused on the space and less on the planetary experience, but I'm more on the planetary side, especially in the first book.

Kol-2, planet from Goodbye to the Sun by Stephen Wood

JP: Tell me a little about your process.

JW: A lot of people like to use two terms for writers: You’re either an outliner or you're an exploratory writer. I would say I'm right in the middle. I start with characters and from a person's point of view. From there I begin to envision a conflict that needs to be dealt with. I start to build the world and then go back to the characters. I rely a lot on traditional plot points; if I'm going to write a 100,000-word book, that means that at the three to five percent mark, there's going to be the hook, and at the 10-percent mark, we're going to get the inciting incident. Act one, act two and act three structure. I need to get from A to B, and I don't know how I'm exactly going to get there. There might be a character who just appears as I'm writing and it's like, oh, where did you come from? I've learned over time to not fight that, but to let that person in and let them do what they want to do. I'm instinctually carrying out some kind of storyline that I know is the right one, even though my rational, planning mind wants to fight it. And so it's a constant adjustment between having a target and being able to let things fall into place.

JP: What would you say are the three major themes of the books?

JW: I would say family versus state responsibility, whether that means a blood-related family member or your cultural community. What's your responsibility to the community versus your individual rights and freedoms? I also think that morality and ethics are at the heart of all three books. Maybe the third would be ecological; there's a relationship between the human species and all other living things.

JP: You go out of your way to talk about gender. Can you tell me why it was so important to make that so prominent?

JW: I like science fiction because it's a form of speculative fiction. It gives you the ability to envision a different world and a different society, and in a different time. But in doing so, it also allows you to explore the potential and possibilities for our own future. A lot of science fiction includes a diverse range of gender in terms of characters and representation, but there's usually conflict there. I wanted to create a world where the future was such that gender was no longer a political issue, that there were other problems in society that persisted, but gender had reached a point where it was wholeheartedly accepted in terms of self-expression. I was partly inspired the by difficulty that we have sometimes as educators, working in classrooms with different communities and you're making sure you understand how someone self-expresses and are aware of that. Often you need to ask and inquire. Was there a linguistic model that could be put into place where people have agency from the start to make it clear to others how they identify, in terms of gender? I wanted to have a world where it was a queer normative universe and everyone was simply being who they wanted to be.

Goodbye to the Sun ebook cover. Cover design by Jessica Moon. Cover Art by Zishan Liu.

JP: Let's talk about what you do here at Moore.

JW: I started here in 1998 as a part-time adjunct professor. Then I became full time around 2004. I've always been in the Liberal Arts department and over the years, I’ve taught lots of different art history classes and a critical theory class. I've taught the sophomore core course, Critical Issues in Modern Contemporary Art, forever. It's often the first time students are introduced to modern and contemporary art. I'm starting to branch out. I'm going to do a story-crafting class that is hopefully appealing to students majoring in Animation & Game Arts and Illustration who are interested in writing, but also students in the new Film & Digital Cinema major. I'm going to do a creative writing class, too, on science fiction and fantasy, which will be fun.

JP: What is the first artist you introduce to students?

JW: Cassils and Dread Scott are the first artists I show them, on day one.

JP: How would you say your work as a Liberal Arts professor at Moore has influenced your writing?

JW: I get a lot of positive feedback on my world building, that people feel immersed in my settings and the description of scenery. I think that comes from so many years of having to articulate verbally visual information, whether in the classroom or in an article. Because of that, I'm tapped in to a descriptive way of building up an image in the mind.

Teaching a History of Fantasy class has been super fun because the students are so into it. They're the ones giving me all the content. Anything from the last 10, 15 years; they're just throwing all these amazing artists my way, illustrators and game designers. It's incredible. I'm learning from them constantly.

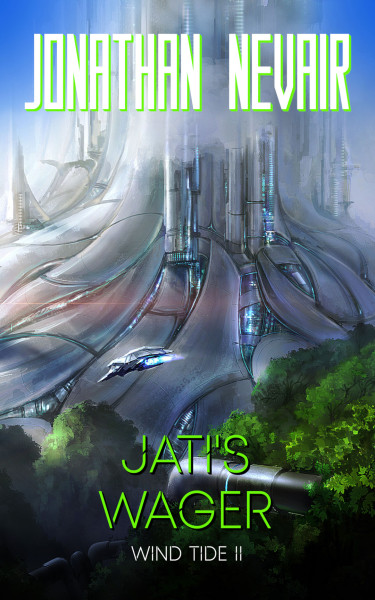

Jati's Wager ebook cover. Cover design by Jessica Moon. Cover Art by Zishan Liu.

JP: Why is it so important that students take Liberal Arts classes?

JW: It’s important for students to be able to articulate their work and their particular approach towards something. Learning how to speak and write, and also understanding their discipline and its history, is very, very important. They need to get up in front of people, to do a presentation, to speak about their work. They might have to write something to apply for a grant or submit a proposal for a game design. We also need to ensure that students have a strong sense of media literacy, so that they can critically interpret the constant streams of information that are coming at us and make a self-determination about where they want to position themselves politically, culturally, morally, ethically and socially. Going through the Liberal Arts curriculum gives them the ability and the tools to do that. That's what we're really focused on: What are the critical core foundational skills and knowledge that students need to succeed? The other thing is being able to lead culturally rich lives, where they're continuing their education on their own terms throughout their lives.

To learn more about Jonathan Wallis, aka author Jonathan Nevair, visit jonathannevair.com or follow him @JNevair.